I am sure that many of us will find a few ‘black sheep’ amongst our ancestors.

These ‘black sheep’ are usually individuals who are seen as troublemakers, failures or just people who do not fit in with the rest of the family. They may also bring disgrace or disrepute upon the family and, in consequence, be considered an outcast.

Although they may have been ‘the black sheep’ of the family, many of these individuals may well have been a much-loved member of the family – perhaps just seen as a ‘lovable rogue’.

Great Ellingham’s ‘Black Sheep’

I wondered whether during the 19th century there were any Great Ellingham families with at least one ‘black sheep’.

Were any of those individuals who were convicted of criminal offences considered to be the ‘black sheep’ of their family? Further, what other misdemeanours would ‘qualify’ someone to be seen as a ‘black sheep’?

Ernest Edwin Rushbrooke

I begin with the story of Ernest Edwin Rushbrooke. Following a fall from grace in 1897, Rushbrooke ‘upped sticks’ and left Great Ellingham for New Zealand. He took with him his wife and children as well as his wife’s sister and brother.

Bury Hall, Great Ellingham. Courtesy of Emma Wilson

Ernest Rushbrooke and Ellen Sarah Wright married in 1884. They made their home at Bury Hall, Great Ellingham. While at Bury Hall, the couple had six children. However, Ernest fell into some disgrace following a liaison with Ellen’s sister Alice Mary Wright, who was employed by her sister and brother-in-law as a live-in ‘mother’s help’.

As a result of the affair, Alice Mary Wright became pregnant.

The story goes that Ernest’s father, Alban Rushbrooke, insisted that Ernest emigrate because of the disgrace he had brought upon the family. Ernest and his family were also forbidden to make any contact with relatives in England.

Consequently, Ernest and Ellen Rushbrooke and their six children left Great Ellingham at the end of 1897. Ellen’s pregnant sister Alice Wright and her brother James Wright also emigrated with the Rushbrooke family.

Soon after arriving in New Zealand, Alice gave birth to a daughter. The child, named Mary Louise Rushbrooke, was brought up as part of Ernest and Ellen’s family.

I have no doubt that the Rushbrooke family viewed Ernest as their ‘black sheep’.

William Kiddle Warren

48-year-old William Kiddle Warren appeared at the Norwich Assizes on the 31st March, 1849. Described as a ‘respectable-looking farmer’, William Warren pleaded guilty to two charges for forgery.

Despite witnesses testifying to his previous good character, William Warren was sentenced to 10 years transportation. Warren was also told that ‘not many years since his life would have been forfeited for the offence‘. In the event, Warren was not transported. On the 1st December, 1853, a licence was granted for his early release.

William Kiddle Warren was indeed from a ‘respectable’ Great Ellingham family. Although I have not found a record of a baptism for William Warren in Great Ellingham, I feel sure that he was born in the village.

Following Warren’s court appearance, his wife, Elizabeth (née Whittred), continued to live in the village. However, despite William’s release, it does not appear that he came back to Great Ellingham. In fact, it seems that he left the country.

William Warren’s father, Thomas Warren, died in 1858. In his father’s Will, William Kiddle Warren benefited from the rental income from one of his father’s dwellinghouses in Norwich. Further, Thomas Warren left specific instructions that the income from the property due to his son should be held for William “in case he shall come to England to claim the same“. However, the legacy must be claimed within five years of Thomas Warren’s death.

This leaves the question – Did William Kiddle Warren ever return to England to collect his inheritance? Indeed, did he ever return to his family?

Although it seems from the witness statements at the court hearing that William Kiddle Warren was previously of good character, was he truly the ‘black sheep’ of his family?

Samuel Terrington

Like many other towns and villages, Great Ellingham saw several of its inhabitants transported to Van Diemen’s Land (later Tasmania) as a result of their crimes.

In 1836, 36-year-old Samuel Terrington received a sentence of 14 years transportation for stealing fowls as well as a gun. This was not his first offence.

Further, Terrington may well have been part of a gang which had “long been the terror of the surrounding neighbourhood of Great Ellingham“.

Was Samuel Terrington the ‘black sheep’ of his family?

I wonder if he was more of a lovable rogue. Within six years of his transportation, Samuel made a successful application to have his wife and children join him in Van Diemen’s Land.

James Denmark & Goodson Pitts

20-year-old James Denmark and Goodson Pitts aged 21, were two other young men from Great Ellingham families who were most likely part of the same gang as Samuel Terrington which, around 1836, brought terror to the community.

Having previous convictions, Denmark was sentenced to 14 years transportation and Pitts a lesser term of 7 years. However, the court was told that there were ‘no less than five charges against them’.

I think it is likely these two young men were indeed the ‘black sheep’ of their respective families.

Susan Pea

In 1837, 26-year-old Susan Pea was convicted of stealing two bushels of turnips. A married woman with children, Susan received a sentence of 14 days imprisonment.

I have not discovered any other court appearances for Susan.

The 1830s was a particularly difficult time for many working in agriculture. The introduction of the mechanised practices resulted in unemployment, reduced wages and poor conditions.

Did Susan Pea steal the turnips to feed her family? Was her husband, agricultural labourer John Pea, able to find enough work to support the family?

Did Susan’s family view her as their ‘black sheep’?

Intemperance Skipper Brothers & Christmas Chaplin

We come to those villagers who were often before the Magistrates for drunkenness and disorderly behaviour. These include brothers Abraham and Jeremiah Skipper, who stood before the Magistrates on many occasions during the 1870s. The charges against them were usually for drunkenness and riotous behaviour.

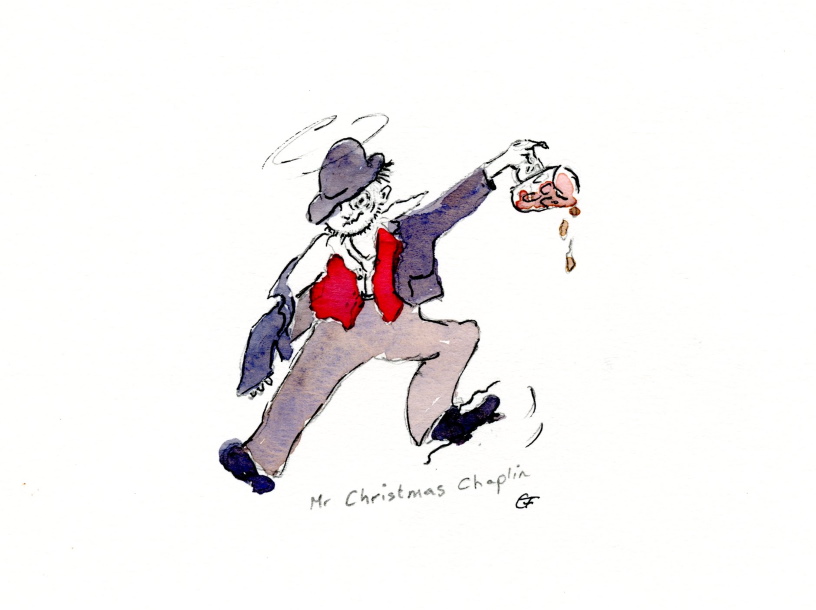

Illustration by Christine Fuller

Labourer Christmas Chaplin was another habitual offender. He was brought before the Magistrates on several occasions for being drunk during the same period.

Were these men considered to be the ‘black sheep’ of their families? I think not.

Many labourers stopped at their local pub at the end of a hard week’s graft, and spent some of their hard earned money on a pint or two of beer. More often than not, a few more than a couple of beers were consumed which resulted in many a villager finding themselves rather the ‘worse for wear’ and, at times, in a brawl before they reached home!

William Yeomans

William Yeomans was 34 years of age when he stood before a Judge and pleaded guilty to a charge of arson. He set fire to a stack of wheat in Great Ellingham in the June of 1879.

William’s case was not straightforward. At the hearing, concerns were expressed around William’s state of mind. Before he was 20, William had been confined to an asylum in Norwich. He was admitted to the asylum again aged 23. During the 1870s, William was brought before the Magistrates on several occasions on charges of drunkenness and disorderly behaviour.

In the event, the Jury at the Norwich County Assizes returned a verdict that William Yeomans was “incapable of understanding the plea he had given“. The Judge ordered that William be “kept in strict confinement during Her Majesty’s pleasure.“

William Yeomans was sent to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum where he spent the next 10 years. By the beginning of 1889, William Yeomans was back in Norfolk. He was admitted to the Norfolk County Asylum on the 10th January, 1879. He remained in the asylum until his death on the 17th January, 1911.

William was indeed a troubled soul. However, given that in those days there was little understanding of mental health, I wonder how supportive William’s family were. Did they regard William as a ‘black sheep’ – which, if they did, it was probably undeserved.

Charlotte Fisher

Charlotte Fisher is another contender.

Great Ellingham Hall 1960s. Courtesy of Susan Fay

18-year-old Great Ellingham born Charlotte Fisher worked as a general domestic servant for Benjamin and Sarah Barnard at The Hall, Great Ellingham. On the 5th July, 1871, Charlotte and Sarah Barnard had a disagreement. Consequently, Charlotte Fisher was given notice to leave.

Illustration by Christine Fuller

However, before leaving The Hall, Charlotte prepared her employers’ afternoon tea. Charlotte put an amount of rat poison in the tea – reported to have been sufficient to kill. Fortunately on pouring the tea, Sarah Barnard noticed that the tea appeared blacker than it should be and it had an awful smell.

Charlotte Fisher was convicted of the crime and received a sentence of penal servitude for life. However, her sentence was later commuted and she was subsequently released from prison within 10 years.

In 1884, Charlotte married Primitive Methodist Minister, Samuel Utting. The marriage did not produce any children.

Did Charlotte’s parents, Joseph and Elizabeth Fisher, see Charlotte as the ‘black sheep’ of their family?

Rhoda Bilham formerly Carter née Dunnett

Finally, I should mention repeat offender Rhoda Carter.

Rhoda Dunnett

She was born as Rhoda Dunnett around 1820 in Besthorpe, a village not many miles from Great Ellingham.

By 1841, Rhoda worked as a live-in housekeeper for 45 year old widower and Chelsea Pensioner Jacob Carter in Great Ellingham. She would have also cared for Jacob’s four young sons. Rhoda’s mother, Susanna Dunnett, also lived with the Carter household.

Rhoda Carter

On the 23rd August, 1841, 20 year old Rhoda married Jacob Carter in Great Ellingham on the 23rd August 1841.

In the August of 1852, Rhoda Carter appeared before a special sitting of the Petty Sessions in the nearby town of Attleborough. She was convicted of violently assaulting Elizabeth Fame. Rhoda received a fine of 5s with costs of £11s 6d (with 21 days imprisonment in default).

It seems that this was not an isolated offence. Rhoda Carter had previously (and frequently) been before the Magistrates on similar charges.

Rhoda Bilham

Jacob Carter died in 1864. By 1870, Rhoda moved from Great Ellingham to Roudham, a village some nine miles away, and subsequently, married widower William Bilham.

In the September of the same year, Rhoda again appeared before the Magistrates. She was charged with assault and threatening language towards Sarah Gates, who was also charged with assault and threatening language towards Rhoda Bilham. Both women were convicted. They were each given a fine with costs. In addition, they were bound over to keep the peace for three months.

Six months later in March, 1871, Rhoda Bilham and Sarah Gates were back before the Magistrates on similar charges. Sarah Gates’ son, James Gates, was also brought before the court.

An assault charge against Sarah Gates was dismissed. However, James Gates pleaded guilty to assaulting Rhoda Bilham and received a fine. Nevertheless, both Rhoda Bilham and Sarah Gates were again bound over – this time with a surety of £10 and were ordered to keep the peace for six months.

Just two months later, Rhoda Bilham was back before the Magistrates. She was charged with assaulting Ann Foreman, also of Roudham. However, on this occasion, the case against Rhoda was dismissed.

Although Rhoda was not estranged from her mother (Susanna Dunnett lived with Rhoda in Great Ellingham), it is more than likely that other family members saw her as a ‘black sheep’.

Conclusion

Having looked at several of the individuals in Great Ellingham during the 19th century, I believe some of the families did indeed have at least one ‘black sheep’!

Full Versions and Sources:

Detailed blogs for the individuals named above can be viewed by clicking on the respective headings. These blogs will also include references to sources.